Will the Captain Roberts Please Stand Up?

This was originally posted on Vivendo de Lembranças, a page which I no longer maintain. There may be small edits or changes below. The original post is available on the Wayback Machine. (C) Copyright Cliff Hansen, 2022.

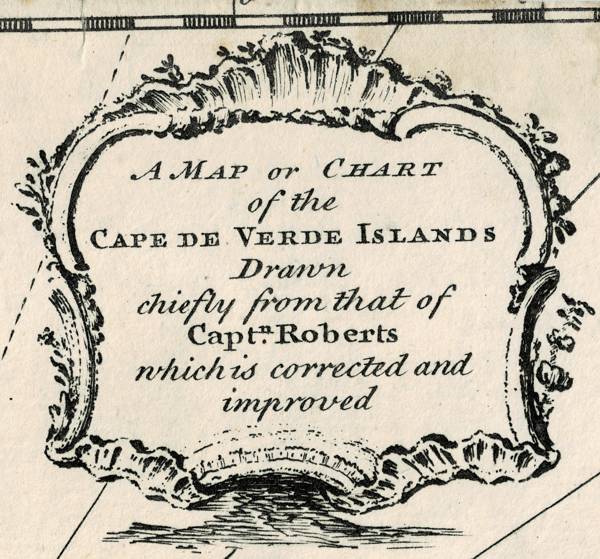

When scanning my first Cabo Verde map for this site (which you can access here), I noted that it was “Drawn chiefly from that of Capt.ṇ Roberts which is corrected and improved”. So who was this Roberts which the engraver Thomas Kitchin based his work on? The short answer is: not a whole lot. But I know who he is not and that’s actually an interesting story.

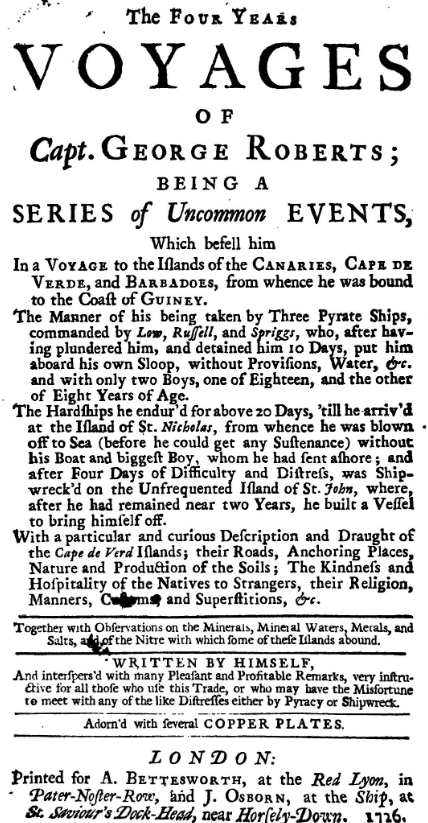

Superficial research brought me to a book which was published in 1726. Its title is as specific as it is lengthy:

Don’t believe me? You can read the book for free here. (Some editions smartly trimmed the title to: A Voyage to the Cape de Verd Islands, &c.“) Then again, you don’t really need to read the title since you already know everything that happens in it!

If you skip all the way down toward the bottom, you’ll see that this Captain George Roberts apparently wrote this book himself. I was excited by this find and while I remain excited to read it, my research has revealed two critical facts one must keep in mind prior to reading it:

- It is fiction.

- The name of the author is a pen name to make the book seem more authentic.

But, don’t let that disappoint you, as the real author of the book is known to be none other the incredible Daniel Defoe! If you’re wondering where you’ve heard that name before, it’s probably because you’ve read a book with a properly-brief title of Robinson Crusoe! Some of his other works include the spectacular Fortunes and Misfortunes of Moll Flanders, A Journal of the Plague Year (which might be interesting to read now), and a whole bunch of books about pirates and seafaring.

Defoe was a fantastic author and an incredible researcher. While he did write to entertain, his books are and should be used to help understand the perceived notion of the world he lived in at his time. I have not read Defoe’s Four Years Voyages book yet, but I do look forward to it, even if its author probably never set foot in Cabo Verde for real because I have enjoyed some of his previous works, and I know he was capable of exhaustive research. Hell, he referred to minerology in the book’s title!

I am certain there is much Defoe got right about Cabo Verde in his book and he was using the best collected knowledge at the time. However, we’re talking about the collected knowledge Europeans had access too. I read comments that many of the descriptions are xenophobic, which is hardly surprising. But there are also reasons to mistrust his details which I’ll address soon. However, there was one thing that Defoe got quite right: he included a map1 which didn’t just look like Kitchin’s map from 18 years later, the two were so similar that it was obvious that Kitchin had traced his map. Here’s a comparison slider where I’ve done nothing but adjust the size of Defoe’s map (keeping the relative size of width and height consistent) and rotating it just a tad to align it on top of Kitchin’s. They match nearly perfectly.

Wikipedia is pretty blunt about what happened here: “Kitchin frequently stole the works of other cartographers, which is one reason why he ‘created’ so much work as a cartographer.”3 And then provides a link to a collection of Kitchin’s maps including an intriguing line: “General atlas describing the whole universe.” If you’re going to provide cartography for the entire universe, who am I to fault you for cutting a few corners!?

I could care less about Kitchin tracing his map. Honestly, if you weren’t at sea yourself, I don’t know how else you would make actually maps other than take the best available map you had access to and, well, trace it as accurately as you could. But the question remains: where did this earlier map come from?

It came from Captain George Roberts.

I discovered a1975 journal article by Manuel Schonhorn entitled Defoe’s Four Years Voyages of Capt. George Roberts and Ashton’s Memorial. Unfortunately the article was behind a paywall so I was unable to read it, but its first page contained a lengthy footnote with the following “Paul Dottin, discovering an actual Captain George Roberts taken by pirates at Cape Verde in 1728, gave Defoe a significant rewriting and editing role and ascribed the volume to him”.2

Thankfully Schonhorn had cited his work, leading me to a 1924 book by the aforementioned Dottin (Daniel De Foe et ses romans) which was available to read for free on Google Books. It was in French which I don’t speak, but we live in a time of technological miracles! From page 776, as translated by Google Translate:

We are able to prove with certainty the existence of [the real Captain] Roberts. On September 7th, 1728, the Journal The Daily ran this snippet, which shows that Roberts had returned to curise the areas he knew good for having suffered so much there: “The sloop Providence (Captain George Roberts) which recently arrived in the Thames, coming from the Cape Verde Islands, was, during its crossing, on the 10th of last month, by 45° of North latitude and approximately 210 of longitude, west of Cape Lizard, attacked by four ships which hoisted the French colours. The sloop flees in vain and was joined. The captains of the assailants boarded the sloop, and, after thrashing Captain Roberts for they had difficulty in joining him, ransacked the hold, and carried away, like pirates, good which, according to a moderate estimate were worth 26 pounds.4

Dottin speculates that Defoe never knew the real Captain Roberts, but was instead given a manuscript which had been written by Roberts. Defoe then revamped the manuscript, composing a narrative on top of it making it read more like an adventure. “De Foe’s role consisted above all in lightening this heavy style by making cuts, by abbreviating certain scenes […] by introducing discussions and dialogues, by condensing and modifying certain sentences […].” He notes that it is difficult to determine “what belongs to Roberts and what belongs to Defoe.”5

It is Dottin’s opinion that “we have every reason to believe that the description of the Cape Verde islands has been considerably augmented by De Foe, a specialist in commercial geography.”6 He details the version Roberts himself had written and given to a bookseller:

The work of Roberts had the success that usually at that time the travelogues, nothing more. No one questioned its authenticity. In the first volume of his New collection of voyages on land and sea, published in 1745, the London bookseller Astley gave a long summary of it, told to the third person, and he recourse to a compiler to develop with the help of the relation of more recent travellers, the chapter relating to the islands of Cape Verde. This collection was translated into German by Schwabe under the title [“A General History of the Voyages”] (1747), the name of Roberts became famous on the continent. The work was republished separately in [the English-Speaking world] in 1815, without however emerging completely from oblivion. It is too commonplace today to interest people other than those who retrace the history of the discovery of the globe or those who draw up a list of De Foe’s works.7

Does this mean that there is a dry, but likely more accurate account of Roberts’ work out there, but in German? This is where my trail went dry, although perhaps more exploring of the German book “Allgemeine Historie der Reisen” will return useful results in both who the real Captain Roberts was, and what the real circumstances of his journey to Cabo Verde and elsewhere were.

So why do we care? It’s important for history to understand who a person was, separate from media which sought to expand and dramatize upon their adventures for the sake of entertainment. In his original account, Captain Roberts was writing through his own lens which included certain stereotypes and preconceptions, and those would all be magnified and combined with those of Defoe to present a view of Cabo Verde that was quite a bit removed from the experiences of the people actually living there.

Please note that I don’t fault Defoe here any more than I would the producers of a movie such as American Sniper or Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter. While they may be creating a layer of fiction on top of a real person, at the same time they are popularizing the subject through their writing which has hopefully inspired others to look into the authentic character behind the scenes. While the authentic story may have been eroded, important clues may remain to a part of time which history may have otherwise not recorded if there hadn’t been a popular writer to record such notes, even if they make it hard to determine fact from fiction today.

Footnotes:

- Daniel Defoe (1661?-1731), “The Four Years Voyages of Capt. George Roberts; Being a Series of Uncommon Events, which Befell him in a Voyage to the Islands of the Canaries, Cape de Verde, and Barbadoes, from whence he was Bound to the Coast of Guiney …,” Lehigh University Omeka, accessed June 24, 2022, https://omeka.lehigh.edu/items/show/3697.

- SCHONHORN, MANUEL. “Defoe’s Four Years Voyages of Capt. George Roberts and Ashton’s Memorial.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 17, no. 1 (1975): 93–102. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40754364.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Kitchin

- Dottin, Paul. Daniel De Foe et ses romans. United Kingdom: Les Presses Universitaires de France, 1924.

- ibid

- ibid

- ibid

- ibid